A reflection on the boundaries between disciplines of Craft, Design and Art. What defines each, and are they much different from the other?

Setouchi Triennale 2025: Part 1

We arrived late in the night on ferry to Shodoshima, and the streets were pitch dark. Not a single street light. We had to use the lights from our phones under an inverted plastic bag to create a temporary lamp while waiting for the bus to our ryokan. Upon arriving, we fell right asleep on the futon, and it was not till the next morning when we looked out the window and saw something strangely out of place— a sparkly disco ball on which a dragon-like creature sat.

Star Anger, 2015, at the end of the pier in Sakate, Shodoshima. Yanobe Kenji.

That was my first encounter with a public ‘artwork’ and with the Setouchi Triennale, though I knew nothing about it then. Little would I know that a year later, I would be making my way back to the area as a volunteer with the Koebi-tai NPO, in 2019 as a staff member, and this year, as a guest— though I always feel like I’m coming back home.

I have encountered the Setouchi Triennale 3 times so far, from 3 very different points of view; and each time has felt very different. While this article would be focused mostly on the Spring season of the 2025 edition, I will also throw in some comparisons from previous years and contextual information. (This is a growing article that will be updated)

This article also serves as a summarised introduction for people completely new to the festival, with helpful links (reservations, bus schedules). There will be a focus on Megijima, Ogijima and Shodoshima, since I feel English information for these is limited compared to the popular Benesse Art Sites.

Introduction to the Festival

Volunteers from Koebi-tai doing mi-okuri (sending off the ferry by waving flags), last day of Spring season 2025, Ogijima.

Concept & Community

The Setouchi Triennale debuted in 2010 helmed by Fram Kitagawa, who had also launched the Echigo-Tsumari Triennale comprising 6 regions in Niigata back in 2000. The plan for Seto-gei (an abbreviated form of ‘瀬戸内芸術祭 Setouchi Geijyutsu-sai’) and Echigo-Tsumari 越後妻有 (also known as ‘大地の芸術祭 Daichi no Geijyutsu-sai’) was the same— to revitalize a region that was suffering from depopulation, and re-introduce a sense of purpose to the ageing locals whose main livelihood (mostly farming) had become undermined by commercialisation and the move into new industries such as technology. “Places exist in space but also in time,” Kitagawa writes, and it is this reason that most artworks of the festivals are site-specific and temporary, considering the direct environment, community and materials. They might not last forever, protected in crates or secure white cubes; yet they create memories and move people.

Another point that makes these 2 festivals different from others around Japan (or the world) is the heavy focus on community involvement— volunteers basically carry the festival, from artwork production to manning the reception desks. The Kohebi (little snake) group in the Niigata area and Koebi (little shrimp) group in the Setouchi area are NPO organisations that serve as an important bridge between the organisers (Kitagawa’s Tokyo Art Front Gallery) and the volunteers who come from all age groups and backgrounds; in the case of Seto-gei, it sees a lot more international volunteers (roughly half of the volunteers are foreign— and no, you don’t need to be able to speak Japanese to join).

This inclusion of the community helps to boost pride and morale in the festival, as Kitagawa believes it is important for the locals to be involved in order to understand and feel engaged to this foreign concept of ‘art’ suddenly appearing in their immediate environment. His plan seems to be proving true, as the locals, however resistant in the beginning, have learnt to embrace the change. Seto-gei is seen as the biggest and most successful Art Triennale in Japan, one that has truly impacted the region hosting it.

Kitagawa has mentioned in his book that the Japanese practiced ‘traveling as a discipline’ since ancient times, but the efficiency of today’s travel has made it ‘a means to cover distance’ and leaves ‘little room for individual effort and creativity’. By spreading the artworks out across the region, the visitor’s experience is guided by the artworks. In short, the artworks are not just a ‘destination’, and serves as a medium for you to interact with the landscape and its changes through the seasons— a deliberate, “inefficient” journey.

“Art should serve some function for the people living in the place... should be integrated into the fabric of the city, as opposed to having some sort of autonomous assertion of its own separate existence...

Art is a medium that can move and transform people.”

Recommended reading: Art Place Japan by Fram Kitagawa

Should I buy the Triennale Passport?

In the area of the Setouchi Inland Sea is thousands of islands, but only 11 are involved in the festival. In total, there are 17 areas to explore, comprising some on the mainland either close to the ports (e.g. 津田 Tsuda, 引田 Hiketa) or which used to be islands before being connected to the mainland by land reclamation (e.g. 瀬居島 Seiijima, a new area in 2025). The festival is also strategically split into 3 seasons, with some regions showing only in certain seasons, appealing to visitors to make a trip back.

Visitors are encouraged to purchase a ‘Triennale Passport’, which allows them one-time entry into all Triennale artworks and most museums, though some might incur extra fees. While it is also possible to purchase individual tickets to specific artworks (available at the reception of each artwork, cash only), the entry price this year has been raised to 500JPY each, making the passport a much more cost-effective option (viewing just 9 artworks would cost 4,500JPY, which is the price of a single-season Passport). The 3-season Passport allows one to view all artworks across Spring, Summer and Autumn, and costs just 5,500JPY. However, if you are living outside Japan, the single-season Passport makes more sense.

If you purchase online via the Setouchi Triennale App, you will be able to use the Digital Passport (unique QR code for each person) on your smartphone; this is scanned at each artwork’s reception counter. While it is much faster and more convenient (you don’t have to worry about forgetting the paper Passport in your hotel room!), you miss out on accumulating the Passport stamps, which has always been a fun feature of the festival. If you have purchased the passport from convenience store machines or online websites that require you to EXCHANGE for a paper Passport, you can do so at the individual artwork reception counters only if you have the PHYSICAL TICKET for exchange— if yours is a QR code, you have to exchange for it at the Takamatsu Port General Information Center or other venues on the mainland. That QR code will not work once you are on the islands, so take note if you don’t want to have reached an artwork and be denied entry.

Important Points (Closure dates, Required reservations)

This article will focus on the areas accessible from Takamatsu: below is a list of the main areas and some important notes (information from guidebook).

All-Season Areas:

• Naoshima: CLOSED ON MONDAYS | Transportation on island: Bus, Bicycle | Some Artworks and museums require advance individual reservations

• Teshima: CLOSED ON TUESDAYS | Transportation on island: Bus, Bicycle | Teshima Art Museum requires advance reservation and separate fee

• Megijima: CLOSED ON 8/20, 10/22, 10/29

• Ogijima: CLOSED ON 8/20, 10/22, 10/29

• Shodoshima: CLOSED 8/20, 10/22, 10/29

• Oshima: CLOSED ON 8/6, 8/20, 10/4, 10/22, 10/29 | Only 1 Café with limited food

• Inujima: CLOSED ON TUESDAYS (and during bad weather)

• Takamatsu Port area: CLOSED ON TUESDAYS; Check website of Shikoku-mura for possible change in opening hours

ARTWORKS/MUSEUMS REQUIRING RESERVATION— Click for Link

• Chichu Art Museum (Naoshima)

• Teshima Art Museum (Teshima)

• Naoshima New Museum of Art (Naoshima— Newly opened in May 2025)

• Hiroshi Sugimoto Gallery (Naoshima— New artwork)

• Minamidera (Naoshima— Part of Art House Project; James Turrell artwork)

• Kinza (Naoshima— Part of Art House Project; Rei Naito artwork)

For the list of artworks above, it is almost impossible to book a ticket on the day itself, so do reserve in advance.

Navigation: Ferries

Map cropped from official site showing numbered routes

• Overall ferry schedule on official site

• Megi-Ogi Ferry Schedule (route #8)

• Shodoshima - Takamatsu Ferry Schedule (route #9)

One friend commented that she would need a doctorate to properly plan for this festival— and it sure feels like it. Even with the guidebook, the numerous ferry boarding points, bus timings, ferry timings, is enough to scare off even Japanese-speaking foreigners like myself.

You are not able to buy advance ferry tickets (aside from the 3-DAY FERRY PASS which you can purchase through the Official App); most counters open 30mins before the ferry departure time. The Ferry Pass does not allow access from Takamatsu to Teshima, only from Uno (Okayama).

DON’T MISS THE FERRY— the timing stated is the timing it SETS OFF, so always arrive at least 15mins before. There are also a couple of different boarding points and ticket sale counters that are situated on the far left and right ends of the port, so be early for some buffer time. There will be 2 queues: 1 to get the ticket at the counter, another to board at the pier. Be sure to queue for the boarding even after you have your ticket!

TESHIMA

From Takamatsu to Teshima (route #6: direct, route #5: via Naoshima), the ferry is small and can take only about 100 people, so many people start queuing 1 hour before. If you are not early enough, you might be pushed to the next departure timing which can upset your plans (especially if you have a museum reservation).

INUJIMA

If you are visiting from Okayama, I highly recommend visiting Inujima (route #13, #15)— there is no direct ferry to Inujima from Takamatsu, so you would have to pass through either Naoshima/Teshima (route #4) or Shodoshima (route #14) to get there. Okayama also has ferries to Naoshima, Teshima and Shodoshima.

MEGI & OGI

Megi and Ogi are accessible by the same and only ferry: setting off from Takamatsu, it reaches Megi in 20mins, then moves on to Ogi in another 20mins (route #8). It is very straightforward, and you can do both islands in the same day. While the ferry can be very packed, it is seldom that you are unable to board from Takamatsu. If you’re planning to do both islands in a day, you cannot buy a round-trip ticket; you will buy 3 single-trip tickets. The price remains the same, but you have the slightly troublesome job of locating the ticketing counter on the islands and buying the ticket (which I recommend you do in advance to avoid the mad rush before boarding).

SHODOSHIMA & NAOSHIMA

For Naoshima (route #1) and Shodoshima: Tonosho (route #9), there is a choice of the big ferry (slower and cheaper), and hi-speed ferry.

As there are limited rental cars on both islands and not all of them are willing to rent to foreigners, renting from Takamatsu and driving up to the ferry is a possibility (additional fees required).

OSHIMA

Oshima is very different from the other islands since it has a very difficult history— it used to be a sanatorium for leprosy or ex-leprosy patients. The ferry is free to take, and usually quite empty due to the smaller number of works.

Navigation: on Islands

• Naoshima Shuttle Bus schedule

• Teshima Bus schedule

• Megijima Bus schedule

• Shodoshima ORIX Rental Car site

NAOSHIMA & TESHIMA

I recommend taking a bus around the popular Naoshima and Teshima if you don’t usually exercise (like me)— the slopes pose a bit of a challenge, even with the electric bicycle. However, that means a lot of planning for bus timings and wandering around the sometimes maze-like island paths trying to locate a bus stop. My advice: Leave A LOT of buffer time for everything, give more time for each spot (and lunch), suss out bus stop locations for the return trip the moment you arrive. There is a town bus in Naoshima, but I recommend focusing on shuttle bus timings, then walking to areas around the bus-stops.

MEGIJIMA

The only location for which you need a bus is the Onigashima Cave, which is possible to trek to but not recommended. There are 2 artworks at the cave, and a round-trip ticket costs 1,000JPY (single trip is 700JPY). Please note there is also an entry fee (600JPY) to the cave even if you have the Triennale Passport. For everything else, it is totally possible to walk as the island is small and relatively flat, though bicycle rentals are available.

OGIJIMA & OSHIMA

Both Ogijima and Oshima are small enough to get around on foot; Ogi has quite a lot of slopes so do expect to trek a bit.

SHODOSHIMA

If anyone has told you it is possible to explore Shodoshima by bicycle or walking, they are either very strong people or lying! I highly recommend a rental car in order to fully enjoy the island as it is huge; 1 night stay is recommended. However, many car rental companies do not rent to foreigners even if you have an international license, so do check in advance. I recommend ORIX Rent-a-Car: they are open to foreigners, and very close to Tonosho port.

This marks the end of Part 1; now that we have gotten the pesky information bits out of the way, the next article (or more) will be focused more on the artworks on different islands and which I recommend.

Transitory Nature of Earthly Joy by Albert Yonathan Setyawan

Plant reaching the boundaries of its enclosed world

There is so much inspiration to be taken from the cycle of life. Every second, something moves, even if we don’t perceive it. While some might argue Time is a social construct, progression is the evidence of our ongoing existence.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan’s work has always had this stoic quality about it that quietens your soul when you approach it, almost as if any unnecessary movement might disturb the unseen energy flowing between his ceramic forms. Our state of awareness is subtly heightened as we are physically dwarfed by the presence of hundreds of ceramic objects crafted by the artist’s hands. What transpires in the space between us? ‘Transitory Nature of Earthly Joy’ is no different; except now there is a movement in the space. Not from us, but from the works.

‘Transitory Nature of Earthly Joy’ at Tumurun Private Museum in Surakarta (Solo) City runs from 8 June 2024 to 12 January 2025. At the point of my visit, the exhibition has been in progress for more than 3 months. Time of visit is seldom a point of concern for visitors, yet here, as the name of the show suggests, your encounters with the work at any point in time presents them in a different state of being. The artist recommends visiting the exhibition more than once to experience their transformations during the 7 month period.

While I was lucky enough to view several of Setyawan’s monumental installations during his survey exhibition “Capturing Silence” in Jogja National Museum (Yogyakarta) last year, those who have missed the show can observe several of his installations and paintings in the collection of the museum on the first floor. Even having seen it before, one cannot help but marvel at its immensity and combined weight of each ceramic piece that might fit in a palm. The presentation of these prior works provide a good context for the transition to the new works, contained in the second floor gallery space.

The 12 new works are an expansion on a previous iteration at the aforementioned exhibition last year, in which 2 urns made of raw clay and other organic material were presented in a clear case containing a controlled environment, encouraging growth in the seeds buried within. The presentation has since been altered to tremendous effect; the source of the water for these individual encased worlds are now almost invisible and the objects sit atop a bed of soil, giving the impression that a slice (or rather, square) of life in the natural world has been carefully removed and contained within clear walls. The sense of witnessing the movement of life becomes more palpable as we put our noses up to the glass foggy with condensation, an inch away from the pill bugs scurrying away with their lives.

First iteration of ‘Transitory Nature of Earthly Joy’ at ‘Capturing Silence’ exhibition in Jogja National Museum in 2023. A tube feeds water through the case which contains the urn, looking like an artefact more than the installations echoing life in the new works.

One understands ceramic as only being complete after the firing process; Setyawan challenges this notion of permanence expected of this ancient medium with his explorations into the destruction— or in this exhibition, undeliberate alteration— of the clay vessel. His video artwork titled ‘Transitory Nature of Earthly Joy’ in 2017 hints at this curiosity to invoke a sense of impermanence using a method that is uncontrollable (in this case, water), having to let go of the tendency to pursue a ‘perfect’ final piece that most who work with mediums of craft origins find pride in. This does not suggest a lack of precision or inadequacy in craftsmanship however; destroying only an object made with care and achieving a certain standard (something fragile, and innocent) evokes that fleeting sense of regret and reflection about the ephemeral quality of life.

Video Still from Transitory Nature of Earthly Joy, 2017. © Albert Yonathan Setyawan. Image courtesy of the Artist and Mizuma Gallery. Image taken from: Monsoonsea.org

In this iteration in 2024, the vessels do not cease to exist completely, but instead presented in an ever-changing state without a final form. The artist acts as an initiator of this ecosystem, involved only with its genesis; the form carries on with life, proliferating in unexpected ways that surprises even its creator.

As an artist who also uses the method of destruction to alter the state of ‘mono-material’ vessels created by hand (in my case, using fire and crochet), I relate strongly with this curiosity that extends beyond the form and technical satisfaction of a piece resulting from precision and control. While our motivations for destruction are different, I find the surprise from the unpredictability of the involvement of a force larger than ourselves (namely, Nature) liberating. Artists and Craftsmen largely differ in that the former sometimes struggle to control the flux in their emotions and expressions; the latter, with letting go of control. In the position of artist practicing in the realm of craft, the balance of control requires immense consciousness to the medium and the voice, which I feel Setyawan has done beautifully.

The new artworks have extended beyond vessels; objects from religious altars familiar to frequenters of Buddhist shrines or temples make up the installations, and is Setyawan’s most obvious reference to a particular entity yet. While his previous iteration in 2023 used urns inspired by those to store ashes post-cremation and hinted at ideas of death and the afterlife, the inclusion of ritualistic objects such as candles, oranges, and a figure of the Bodhisattva is a clear sign to us that the artist is considering the beliefs of the Buddhist religious tradition.

“I have chosen these objects because I think they are a clear and poignant representation of the belief of the afterlife... these objects are usually built to last, commonly believed as representing the connection between our world and the world of the ancestors or the spirits, are juxtaposed using materials that will not last and will continually change over time.”

While we are in the gallery, a slight earthquake tremor causes a quiver; the lamps shake slightly, and the water in beneath the works ripples, despite being in an enclosed tank. We are momentarily shaken from the solemn atmosphere of the gallery, by yet another phenomenon we have no control over. I was struck by how little we seemed at the moment, powerless, just like the bugs and microscopic organisms living within these isolated worlds, experiencing that tremor on a different scale.

I admire the genius of artists who manage to replicate life in the gallery, forcing us to observe and reflect upon the most common and natural phenomenons surrounding us, and which we can so conveniently ignore. Would we normally want to be this close to life, in daily life? Would we want to put our noses so closely to the soil, stare so closely at patches of fungi, if we could smell it? Removing some of the perhaps uncomfortable physical sensations ironically allows us some mental space to access questions of existentiality, rather than just living it.

At times, the work is obscured by the condensation on the glass; frustratingly elusive. We make out a silhouette behind that fog. That inability to clearly perceive nettles the modern human, used to certainty and focus in life and on your screen; this time, this lack of control is experienced by the viewers. This work is meaningful in that it does not tell us what to think, or what it thinks; it just is. We are forced to contemplate the starkness of life and its state of impermanence by putting a glass between us and ‘it’, becoming an observer from the ‘outside’.

This exhibition also includes 3 ceramic installations that are recognizably Setyawan’s; I conclude my visit with the long line of Bodhisattva figures lining one wall of the gallery. Quite small and subtle, I am drawn to it only after repeated observations of the clay-and-soil installations so extraordinarily still yet bustling with life; the Bodhisattva figures are oddly stark and inert after witnessing the wilderness of plants and decay. Yet, walking from one end to the other, you see the barely-there smoothness of an indistinguishable figure gain detail, and it dawns on you the cleverness of the artist at being able to express movement, growth, and transition through objects that by themselves, are in a permanent state.

Ceramic figures on the far-right end of the installation

Ceramic figures on the far-left end of the installation

I believe that artists are translators for the voice within into their medium of expression. The notion of time and progression is difficult to express with with sculpture— something so solid, wordless, and permanent seems to tell you nothing and everything all at once. Setyawan has employed video as a medium in the past, to present the ‘lifetime’ of his vessels as they moved between states of being. In this exhibition, the transition is experienced through the point of active observation, and not through the mode of presentation, which hands the autonomy to the viewers. Watching a video makes us aware we are in the state of witnessing something outside of ourselves; this engagement instead brings forth awareness that what we are observing exists in our very lives.

Art Ripple Taitung 2024: Residency

Linked, 2024. Crocheted ramie dyed with shulang, woven yuetao / Photo credit: #南島漣藝

Documentation of experience in Taitung, Taiwan, for the art residency Art Ripple Taitung focusing on the Taiwanese aboriginal crafts and Austronesian culture. Learning the process of harvesting ramie fibre, dyeing with natural plants, basket weaving with yue tao, and more from Abus Bunun Traditional workshop. #南島漣藝

La Wayaka Current (Desert) 23: Reflections & Artwork Development

Licancabur and Lascar, Coyo, Calama (Chile). October 2023

October 6 - 26, 2023

La Wayaka Current (Desert) Residency Program in Calama, Chile

My obsession with the desert started far away from Chile, when I first started researching about the Gobi for an art biennial known as Land Art Mongolia (I was shortlisted but it got cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic). I have always been interested in residencies in foreign landscapes, and a year after I sent in my application, I was on my way to Santiago, Chile, my first time in either of the Americas.

Physical distance is a strange thing. When I touched down in Santiago after 30+ hours of flight and transits, my life in Singapore felt like years away. I developed a vague understanding of what people said of time and space being linked; somehow, my memories from literally 2 days ago were fuzzy, and felt unrelated to who I was at the moment.

View from plane window, en route to Calama

At the tiny Calama airport (2h flight from Santiago), a small group of strangers convened with bulky bags— the other airport dwellers (aside from the stray dogs we would soon be accustomed with) seemed to be from the mining industry. It was so lucky that almost all of us (in the group of 12) came from different countries; Japan, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, Canada, Australia, just to name a few. I immediately felt the excitement I always do when meeting people from different countries, for I know it promises a variety of perspectives.

The first long drive to the residency was a film, which ended at the boundaries of the pick-up’s window. My face froze with the wind, but the colours of the sky as we chased the sunset were like nothing I had ever seen before. Vast expanses of sand, dotted with ‘shrines’ for those who have died along the road, and scatterings of windmills.

Windmills in the distance

We finally tumbled into the house, located in a little town called Coyo; I remember the dogs welcoming us with barks, a little bit of talking, and then I was asleep. The next morning was our first breakfast experience at the large communal table. The bread and cold cheese, granola and yoghurt looked a bit dismal. But that was only the beginning of our great breakfast expeditions. Soon people were discovering the stovetop bread toaster (which could produce grilled cheese toasties and banana French toast), introducing avocado and homemade salt from the local plant Cachiyuyo. This plant survives by using the stronger roots of other plants for support, but also absorbs the salt from groundwater so other plants can survive. In other words, they have a symbiotic relationship, and thus the Cachiyuyo is seen to be very important by the locals. They are everywhere in the desert, and one of the staff members had ground up the salty leaves of those in the residency garden to use as table salt, adding to our delicious vegetarian meals.

On one of the first few mornings, we attended the Ayni ceremony, to give our offerings to the land. As Carlos, a local healer and our host performed the ceremony in the cold of desert mornings, I was struck by how similar the beliefs were to what I read about the Mongolians. Largely, it reminded me of the balance of Yin&Yang, as Carlos spoke about the balance of woman and man, death and life, dark and light. It also reminded me of concepts of dark, light, death and life in Ursula Le Guin’s The Tombs of Atuan (even more so as it is based in the desert).

I was particularly taken with the concept of Warmija (spelling differs as it is passed orally)— the perfect harmony that can be found between woman and man, resulting in one balanced being. There is also the belief of Pirgua- a single being that can be Warmija on its own. Carlos shared about how Pirgua are seen as blessings; he has a goat who has the head of a male goat, but the genitalia of a female goat. As male goats are aggressive, they often injure female goats while trying to mate. Carlos thus puts this gentle yet playful Pirgua goat into the enclosure with the females to get them ‘into the mood’, and only allows the male goats to ‘finish the act’. I knew at once that this was going to be the basis from which I created my artwork in the desert.

Carlos setting up the Mesa

Facing the grand Licancabur volcano, Carlos laid out a cloth representing a table, with vessels with ‘female’ and ‘male’ faces on them. Right represented life; Left represented death. We made offerings of coca leaves and red wine, respectively putting the offerings in the male vessels with our right hand, and the female with the left.

We were situated only 10 minutes walk from the desert, and most of the residents took morning or evening walks, going as far as the Moon Valley. I am glad for them because I was so engrossed in my work, I did not find the chance to walk around very much. One of the residents, the Danish sound artist Annegry was leaving after 10 days, and I was very glad to be a part of her work in which sand, stones, and other material were used to create a soundscape.

Us trekking across the desert to the Moon Valley (about 45 mins away; I got very burnt!)

Photo of me by Annegry, helping out with her sound installation in the desert

On Annegry’s last attempt, we followed Camilla to a secluded spot in the Moon Valley (about an hour’s trek from our home), where we sat in stillness to listen to the salt in the rocks crackle. The clayey soil there was so soft that if we had shouted, they might have crumbled. It was a wonder to see the magnificent formation of soil, marks of the water erosion from when this same place was under the ocean thousands of years before, stones and mica embedded everywhere. On my very last evening, I did one last trek to the Moon Valley with Elizabeth, where we chose a crevice and clambered up the clay to a private little cave, where we got marvellous views of the desert. It always calmed me to see the volcanos Licancabur and Laskar in the distance, and even more so in the evenings when they were dyed a musky pink. This was also why I chose Licancabur as the motif for one of the artworks I created during the residency, as I saw it as a ‘mother’ figure, overlooking us everywhere we went.

Sunrise silhouetting Licancabur on the morning of the Ayni Ceremony

At a certain point, I was starting to see desserts everywhere we went. It began during our visit to the salt mountain— the solidified salt formed a thin layer above the soil, which cracked as we stepped on it. Our footsteps sunk into the brown dirt beneath, as you would imagine a brownie with a chewy centre, generously sprinkled with icing sugar. The salt layer snapped like a well-baked tuile. The tiny stones presented themselves as chocolate rock candy. The soft soil that crumbled down the mountain was milk chocolate powder.

These photos were taken at the Tebenquiche salt flats, one of my favourite sites that we visited. The colours were just astounding.

Annegry shooting with her vintage camcorder

Another site I loved, an oasis with waterfalls in the middle of a desert valley

Holes in the ground used for ancient constellation-gazing

We had a night’s camp in the desert, where Carlos spoke about the constellations as seen by the locals, and I regret that I was so incredibly sleepy that I couldn’t catch the names. However, I did notice how different the positions of the stars visible from Singapore were. Living on the equator, the sky looks almost the same all the time; yet the sky in the Atacama looks different just ten minutes apart. Doze, and Orion has climbed up from below the horizon. Glance away, and Jupiter has risen. In the Jerez Valley, Carlos showed us large, round-bottom holes that had been carved out of the rock. They had been filled with water, and the pools had been used to read the constellations in the sky so they would know if the skies had shifted.

It was on the very last morning, at 5am while we were driving away from Coyo that I peered out the window looking for the moon. It didn’t seem to be there, until I looked out through the back window of the van— there was the moon; a peeled apple, sinking into the cushiony shadows of the mountain range as it bade us goodbye.

One of the petroglyphs we saw at Jerez Valley

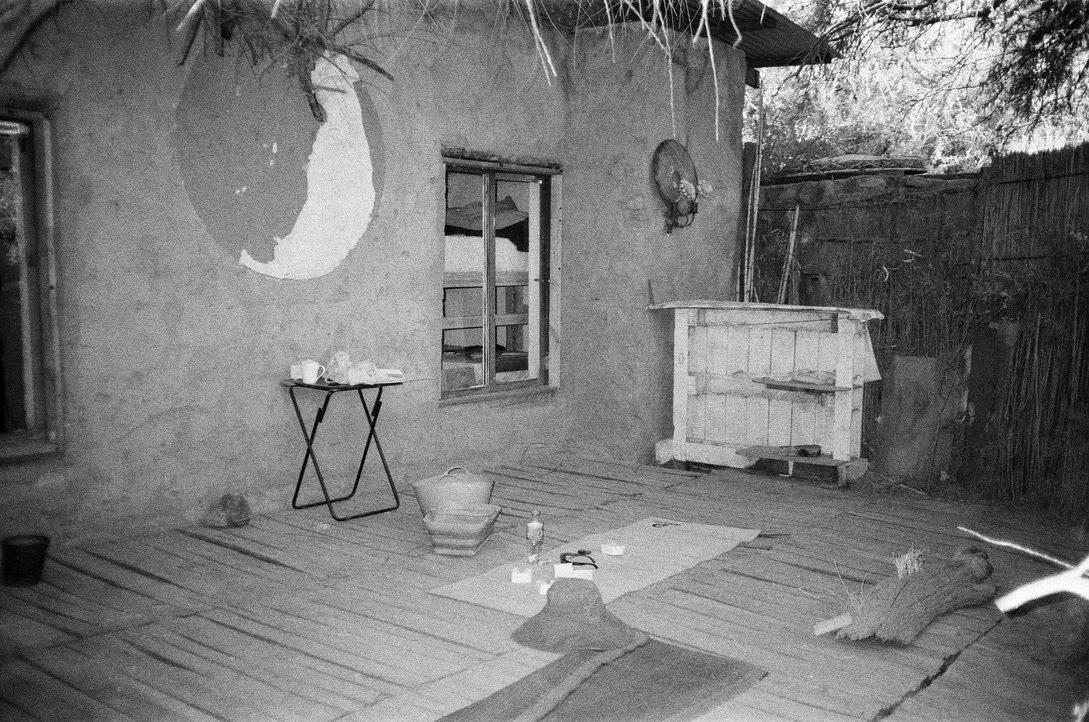

Photo of our ‘studio’ by Annegry

In between our trips to many different places, we carved out our own working spaces in Carlos’ and Sandra’s house, made by them using local materials like river stones over the years. Annegry started working in a little deck at the back of our shared room, and it became our little ‘studio’ space. It was terribly conducive and I started doing yoga there on a new handwoven rug I had bought. As I am rather still as I work, the cats and birds would often saunter or fly past, ignoring me completely. I’d stare up into the dry branches of the tree as I worked. And the best part of all was being completely disconnected from the internet for 3 weeks. We had a particular place in the garden known as ‘cyber’, where connection was strongest (but hopeless on weekends), and one particular chair at the dining table that seemed to command some connectivity. However, I found it was much easier to just work with the fact that there was no connection, and my time at the residency was incredibly productive.

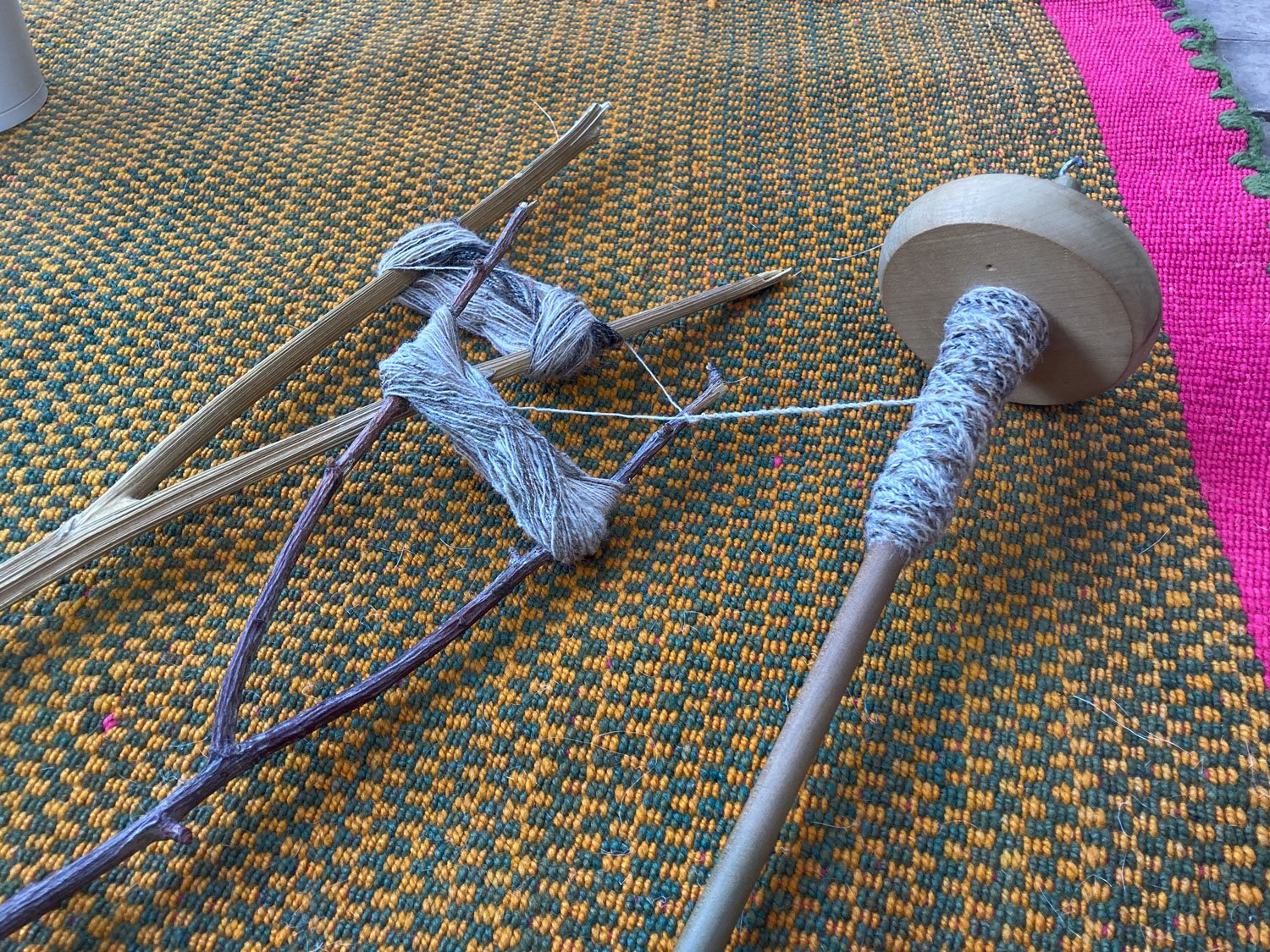

Freshly shorn sheep wool at Gina’s place

We were also very lucky to get a last minute workshop with Sandra’s aunt, Gina, who showed us the shorn wool from her sheeps, and how she spins yarn. I had already begun my own spinning then, and was struggling very hard at cleaning it. While I was desperately looking for a carding brush, which they didn’t sell in the region, Gina’s way was simply to pick out the unwanted matter by hand if she came across it. I learnt from Gina that she used the fibre as-is, and only washed it after the spinning and knitting was complete. The natural ‘wax’ on the fibre helps to hold the yarn together when spinning. It was also impressive that she was using a completely primitive supported spindle for her yarn; I am reliant on the hook of my drop spindle, and while I managed to create a length of yarn with the supported spindle, I reverted to my drop spindle for my actual work. She also sold us precious cactus spine needles, which I had been so keen to get my hands on. Her personal set, having been used for years, had developed a beautiful translucency.

Llama fur caught on branches of low trees as they graze

Huge cactuses at the altiplano, from which the cactus needles are gouged out from with a knife, then burnt at the tips

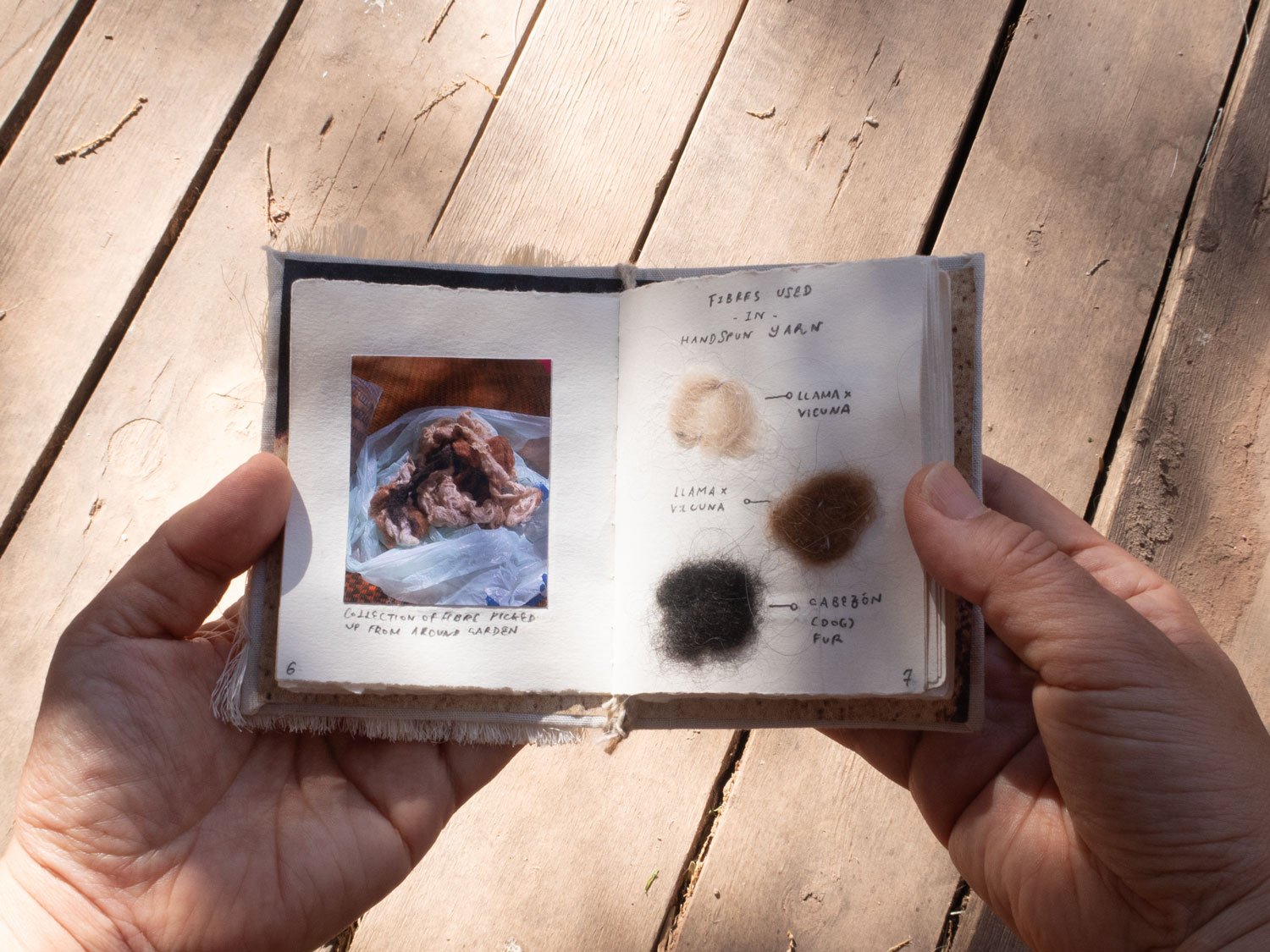

Process of creating II

The above are some images of the fibre I foraged from around the garden (mostly the house dog and the tame vicuna-llama breed), and the 2 single-ply yarns I spun and wound onto Y-shaped branches, then plied into a 2-ply yarn ball. Single-ply yarn are often not balanced as they are twisted in one direction; plying 2 of the same direction in the opposite direction balances and stabilizes the yarn, another interpretation of the Warmija concept.

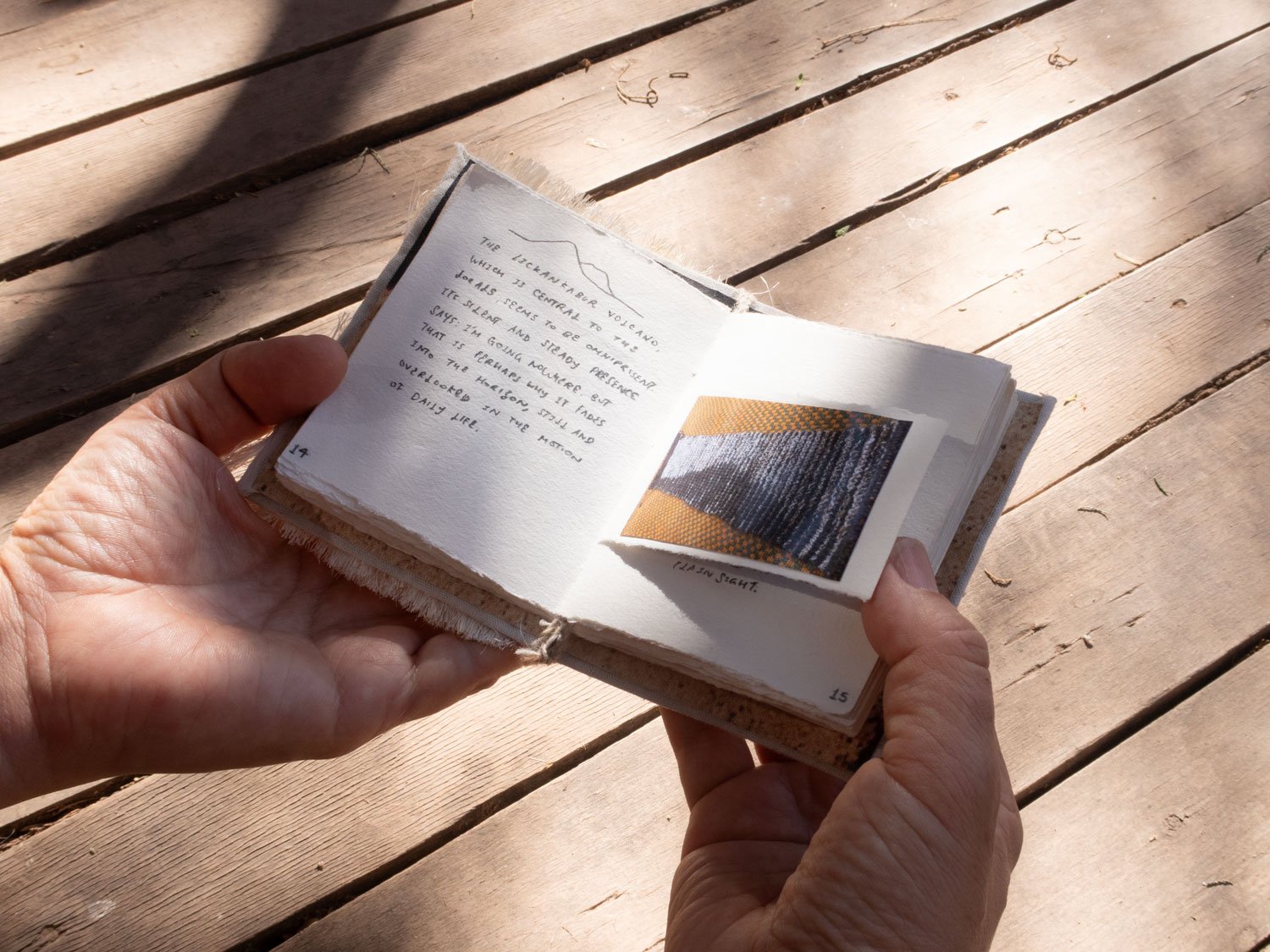

II, 2023. Yarn (llama-vicuna-dog fur) spun on hand spindle and locally-sourced alpaca yarn knitted on cactus needles

Image of II when viewed from the front

I decided to name this artwork II because it has more of an imagery of duality than the numeral 2. This knitted tapestry hints at the silhouette of Mount Licancabur, which reveals itself when viewed at an angle. Similar to how the shadows of mountain ridges change with the position of the sun, I used knitted ridges to create 'shadows' that form an illusion of the volcano.

As I mentioned, I saw Licancabur as a motherly figure; central to the local people, it seems to overlook the scene wherever we go. Its silent and steady presence tells us it is going nowhere, and perhaps that is why it fades into the horizon, still and forgotten in the motion of daily life, just as it hides itself in plain sight on the tapestry when viewed straight on.

The yarn I spun acted as the ‘light’ part of the tapestry; I sourced local alpaca yarn for the ‘dark’ parts. They were knitted and presented on cactus needles, which are of a fixed length and usually used in the round for circular knitting (socks, gloves).

Presentation of II, a sample of single-ply yarn, and a process zine during the exhibition in San Pedro town

Process of creating Mother’s Ritual

During our first introduction to the garden, I found myself spotting many long-fibre plants that could potentially be turned into spinning fibre. The one that caught my eye was the Malva plant, which has a beautiful flower and very long stem. I soaked the stems in water, then used a stone to crush the hard material within; incidentally, I discovered that the ‘foamy’ inner part of the Malva plant created a slimy consistency when in contact with water, which could be used as glue. I also learnt from the locals that they used this in the past to make marshmallow!

Process images of laying out the Malva fibre, drying with twigs and stones

Initially, I intended to collect enough Malva fibre to spin, but my skin was responding very badly to the dry climate and started cracking open. I could not continue soaking my hands in water and peeling off the fibre any longer as the water was going into all the cuts and cracks, and they refused to heal. Thankfully, I had brought along a bag of banana fibre from Singapore, and decided to use this with the Malva fibre to create an artwork ‘from the land, for the land’. In Singapore, due to the lack of space and permissions, it is difficult to create artworks in the environment and just leave them there, so I knew it was one thing I wanted to try while I was here. In the garden, I managed to forage a piece of cactus wood, which had long lines of holes in them resembling pores of the skin.

The above photos are my explorations preparing the rehydrated Malva fibre and banana fibre for ‘planting’ in the cactus wood. I also tried different styles of braiding; in the end, some of the braids were unbraided so the fibre took on a ‘permed’ appearance.

The huge cactuses at the Altiplano that also seemed to me like maternal figures, watching over us. The tiny cactus flowers would emerge from these ‘mothers’, and I saw it as a symbol of birth and fertility even in such tough conditions.

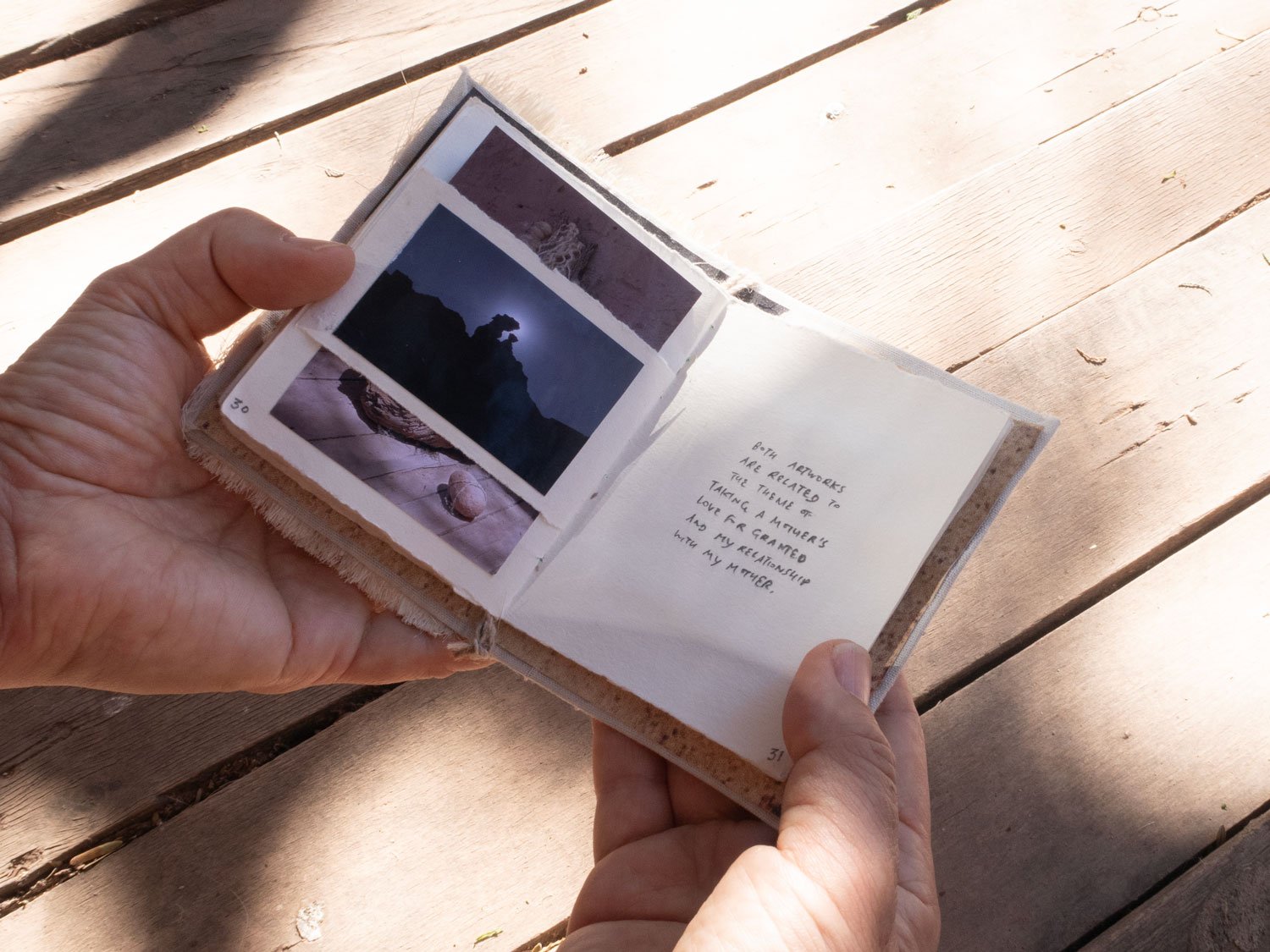

Process Zine

Malva flower

Due to the mode of presentation and language barrier (as most locals spoke only Spanish), I decided to create a process zine with photos so people could better understand my work. As I did not prepare the appropriate tools for binding, I had to make do with makeshift materials such as a repurposed paper bag for the cover, scrap cotton fabric from the garden, and pages torn from my personal sketchbook.

I wanted to include actual samples of the fibre pre-spun, and show the different appearances of the single and double ply yarn so people could understand the process even without words. I also wanted to find a way to include the painfully prickly yet beautiful fibres of the Malva flower. Pulling them out from the middle, I arranged them so one can see the beauty of its subtle gradient.

Both of the created artworks were inspired by and centred around the theme of motherhood; the natural act of protection, and how we often take this relationship for granted. This photo, which I shot at the salt mountain on our first field trip, seemed to be the perfect imagery for the mother-child relationship I have been exploring in my practice.

Me, Licancabur, Mother’s Ritual, and a little rock

When I got back to Singapore, I found that everything appeared to me in such high contrast. The greens of our trees became intense; the lines of the buildings vivid enough to hurt my eyes. I remember seeing my first view of the mountain range in Coyo upon arriving and thinking, oh I hope the sky is a little less foggy tomorrow so I get a clearer view! It wasn’t till a couple days later that I realised, this was the view. Was it the amount of sand in the air, throwing the light refractions off? The colours of the desert, and the softness of its lines, the flow of its sands, the curves of its shadows. How the light caressed each rock, each stone, teaching our eyes new things. These I will never forget. The silence, made with the whispers of the breeze. Feeling the first tickle of the sun, while freezing my toes off in the morning.

I will be back, surely.

This residency was made possible with the support from National Arts Council Singapore.

The Banquet (Exhibition Essay)

This essay was first published online on The Banquet’s website, for the solo exhibition of visual artist AMIEN in July 2023, produced by Kelly Limerick and involving 5 artisans and a musician in an alternative mode of presentation. Please access the photo documentation of the show using the button below:

Text by Kelly Limerick

“Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. At all counts, it forms an unconscious snag, thwarting our most well-meant intentions.”

The Banquet depicts characters caught up in the bustle of the daily grind, involuntarily gravitating towards an inconceivable force visually represented by a black, spherical mass. Taking inspiration from Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of the Id, Ego and Superego, AMIEN creates personas representing these different roles, seeking a semblance of balance in the Universe as they play out their parts like clockwork in the confines of their comfort zone, adrift in a sea of the subconscious; all in spite of the urgency to face the elephant in the room as the fabric of reality begins to split with the expanding black mass.

The black mass does not have a fixed identity, and is represented by a ● symbol; in writing, plural tenses are deliberately used to refer to the mass as a second person pronoun, yet it represents an entirely new entity aside from ‘you’— the reader. Who exactly are ●? This mass takes on different identities for each and every person; a manifestation of avoidance that we will have to confront in time. What is this darkness we fear, and instinctively refuse to face? While it is death that ultimately claims us all, it is also the knowledge of this fact that motivates us to seek meaning during our time on Earth.

‘I’ refers to the ‘self’; a first person perspective, yet not necessarily representing singularity. In this Universe, different iterations of the self are bonded by an unsaid law, each resolutely carrying out their individual tasks. The differences in the appearances as well as behaviour of each character echo the varying facets within each human being; while conflict might arise, they ultimately converge into a single frequency: the self.

Yrasa Idun, © 2023 AMIEN

Growing up in the digital age, AMIEN recognises digital art as a current and relevant medium of our generation. While artists now struggle between remaining purists of traditional art and suffusing all kinds of new mediums into their work, AMIEN chooses to embrace both, propagating knowledge from tradition, and combining it with techniques relevant to our age.

Believing in maintaining a balance between what has been and what is to be, the artist’s oeuvre reflects a marriage between traditional and modern motifs, drawn from his exposure to different cultures growing up in the melting pot of Singapore– yet not a particular one. He expresses that he avoids direct pictorial references, and instead begins the process by daubing colours on a canvas, then refining the details drawn from his subconscious memory. Allowing the colours and emotions to lead his brush, building layer upon layer, he carves out a new path with each new stroke. He considers this style of painting ‘freeing’ as he responds actively to each moment; no one definite truth exists.

While his artworks are woven through with absurdity, the overlap with our human world allows us to develop an empathy for these characters that look so much like us. In the pandemonium, each character is lost in their own personal struggles, swallowed in the chaos– a speck in the Universe. Blue skin and horns aside, the expressions of these characters as they toil on in their daily routines even in this dream- like state, remind us of ourselves– what am I truly working for, and what dwells in my personal shadows?

While AMIEN’s portfolio leading up to The Banquet has seen its fair share of surreal characters, his new work evolves from dainty, still portraits to an outbursting of vigour. Each character is captured in a moment of action with their surroundings hinting at their personal stories, evoking their emotions, ambitions and relationships beyond pleasing aesthetics. An obvious thread of fate ties them all together from painting to painting; a leap from the loose, lone figures of his prior work.

Svakadar, © 2023 AMIEN

Hvasa, © 2023 AMIEN

Beneath the richness and action of the scenes, AMIEN’s experience and obsession with the human form is evident in his vivid rendering of the details. A glint in the eye, a light flare throwing a face into relief, the softness or wrinkles of skin; the artist retains the lessons of traditional mediums and, beneath the surreal imagery, builds a strong base of realism. His evident mastery in balancing shadow and light breathes life into each scene; flames dance and almost crackle with a ferocity in Svakadar, as the harsh shadows lend power to the fire; Saya captures us not with her gaze but the sharpness of her bite into flesh, with the crisp line of a shadow cast across her face.

Saya, © 2023 AMIEN

The curious meat plant in Saya, also making an appearance in Hvasa, first took root in AMIEN’s earlier works prior to the show. In The Banquet, the plant appears to be based on the Peaches of Immortality, a popular icon in Chinese art and a symbol of longevity. While motifs from various cultures within Asia and the physical features of the characters give this Universe its oriental impression, it is the use of straight lines in most pieces creating a linear perspective that reminds us of the uki-e genre of Japanese woodblock prints– which, incidentally, was created through a study of western conventions of perspective. AMIEN uses these lines to construct frames within frames, making the viewers peer at his characters through distant windows shrouded in secrecy.

Aumirvasati, © 2023 AMIEN

Aunhir Mesa, © 2023 AMIEN

The art world has given birth to countless new styles of work thanks to cross-cultural studies of art styles throughout history, and the spirit of innovation. The paintings are woven out of Asian threads, but subtle references to Western art break the monotony of the weft; in Aumirvasati, one cannot deny the presence of the traditional nude under the mint hue of skin with her eyes cast skyward, a characteristic of medieval art depicting religious faith. A shell forms her throne, a re-interpretation of the classic scallop shell in Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus.

Concluding the exhibition with the centrepiece Aunhir Mesa, one could be reminded of the ascension scenes in Christian art where characters coalesce around a rising central figure alight with a surrounding halo– except in inverse. In removing the central figure and the light that surrounds it, presenting us a gaping abyss, we are again made to question what we actually worship in life.

“There are two that make one: the world and the shadow, the light and the dark. The two poles of the balance. Life rises out of death, death rises out of life; in being opposite they yearn to each other, they give birth to each other and are forever reborn. And with them all is reborn, the flower of the apple tree, the light of the stars. In life is death. In death is rebirth. What then is life without death? Life unchanging, everlasting, eternal? What is it but death– death without rebirth?”

In a city like Singapore where art might be considered non-essential, what exactly is the role of an artist? As artists struggle to define their identity and differentiate themselves from machines that convert your worded fantasies into images, they must remember that they are artists because they are making art, and not because they have made art. While A.I.-powered image generators make a beeline for the ‘perfect’ piece of art, humans stumble a hundred steps behind, encumbered by vines of self-doubt shackling their ankles– living a life worthy of a protagonist in literature. Perhaps, like how life and death are irrevocably bound to each other, the creation of machines that strive to be like us, our nemeses, serves only as an example of what we could be upon ignoring the thing that makes us human– our contradictions. What is Life without tragedy? As the Savage in Brave New World (Aldous Huxley, 1932) proclaimed,

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin... I claim the right to be unhappy.”

Life after all, is a destination unknown. The artist walks on, every stroke becoming a step further into his own Universe, one even he has no answers to. He paints, because he wonders, and he wanders, because he paints. It is the same thing.

Artisan Collaborations

Ceramics: Rei Minagawa, Un Studio

The chicken as a phoenix, the lobster as a dragon; homonyms have always been used by the Chinese to transform great mythological beings out of common beasts. Buried in the layers of the complicated Chinese language, the fanciful titles transform any humble, mortal dish into a symbol fit for the gods. The excessive nature of Chinese banquets and the obsession with the act rather than the intention resulting from it set the scene for The Banquet.

In this feast, it is for the symbol that the characters consume, and not nourishment. The table is set with ceramic wares created by local ceramicist Rei Minagawa (Un Studio) in response to AMIEN’s paintings, playing along the same threads of unfamiliarity within the familiar. Inspired by the sancai (three-coloured) ceramics of the Tang Dynasty, the vessels are suffused with a subtle regality; yet they remain warm with the nostalgia of the ceramicist, who introduces the greens of Oribe wares gleaned from her childhood memories of family dinners in a tiny neighbourhood izakaya in Japan.

Yet within them lies nothing but a curious glyph. Upon scanning these glyphs, which function as AR (Augmented Reality) markers with a smart device, the delicacies come into being on a different plane, bridging the ancient art of ceramics to our modern world. The bizarre dishes, created and sculpted by AMIEN with the help of web technologist Siah remain to be enjoyed only with the eyes, giving the vessels holding them a greater sense of physicality once we put our devices away.

The Book from Before. Artwork: AMIEN, Book: Mandy Tan, Derrick Ng.

At the core of it, who governs this Universe, if anyone at all? The Book from Before gives us a hint of the law in motion in a delicate illustration by AMIEN, inspired by ukiyo-e prints. Translated as ‘pictures of the floating world’, this Japanese genre of art usually depicts hedonistic pleasures of the mortal world, and are traditionally printed with carved woodblocks. We are able to imagine the process of this printing method by observing the assiduous craft of printmaker Derrick Ng on the carved covers of this codex, which also functions as a woodblock featuring the imaginary Sira script. Paper conservator Mandy Tan introduces an Asian influence with the accordion fold popular in ancient Chinese manuscripts, and by lining Japanese kozo (mulberry) paper on both sides with Chinese silk featuring phoenixes– the symbol of an Emperor– in flight. Made using the traditional wet-mounting method of Chinese scrolls, the book carries history in its supple yet crisp pages, which when joined end to end, forms a never-ending loop.

Frame: Liuyang, Un Studio

The story concludes on the Aunhir Mesa, the centre of the exhibition and this fantastical Universe. While the characters are being whipped away by the force of the black mass, the painting seems to be weighted down by the one thing holding it– the wooden frame that brings with it a sense of age and stability. Deceptively simple on the first look, subtle curves surface as you move around the frame. Contrasted against the darkness of the core of the painting, the wood— which had been ebonised and stained by Liuyang (Un Studio), flits delightfully between shades of charcoal and warm wood, revealed through a hand-chiselled texture. Organic and inconsistent, the trace of a crafter’s hands in its making gives this piece a convincing history.

Surrounding us with an intangible and invisible, yet unmistakable presence– a metaphor for the black mass– is a soundscape titled Swallow, by musician weish. The composition ushers us into a full immersion of this alternate Universe, conveying the joy and verve of the Banquet as it rages on in spite of a darker, looming entity.

Joana Vasconcelos

Royal Valkyrie, 2018. Summer Exhibition 2018 at Royal Academy of Arts (London)

(All other Artwork photos courtesy of Joana Vasconcelos Website)

This first photo really does not do the work justice, but I decided it should be the header image— because I shot it. I remember walking past the entrance of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, deciding not to go in— and then this caught my eye. I kept trailing about in front of the entrance because it was closing time, and finally decided to make changes to my plans and come back here a couple of days later.

I did not regret it.

Visiting the Summer Exhibition changed my life. Grayson Perry was curating that year, and the walls were a cheerful yellow. The art wasn’t boring. They made me gasp, and laugh, and time flew by. And this! I just kept coming back to it.

As a crochet artist, I am quite picky about the kind of textile art I like. Sometimes, knowing the technicalities makes things a little less impressive. But some work just takes my breath away, because I think, “I would NEVER have thought of that,” or “I have NO IDEA how they did that”.

Joana Vasconcelos’ work is one of those. It isn’t just the sheer magnificence of her large installations such as the one I encountered, but her entire portfolio that has me nodding away and putting my nose up to my screen surveying details. I love consistent artists; a stable line of thought and honesty to the self that runs through all their work, whether big or small, 2D or 3D. And Vasconcelos is not just a textile artist, but uses textile as one of the many mediums in which she expresses herself.

It is clear that contemporary artists require more than just a stoicism towards their craft to bring their work to another level, and Vasconcelos proves that with her 25 years of practice. While she is recognised for her popular work like the Valkyries series or doily-wrapped animal statues— no doubt showing a deep understanding of the medium— it is her other assemblages and kinetic installations that gives me a dose of the artist’s wit, which she uses to ‘[create] a bridge between the domestic environment and public space’.

To be an artist like Vasconcelos, who was the youngest and first ever female artist in the Palace of Versailles in 2012, I imagine dedication, discipline and an organised mind— things so underrated, but so important in artists.

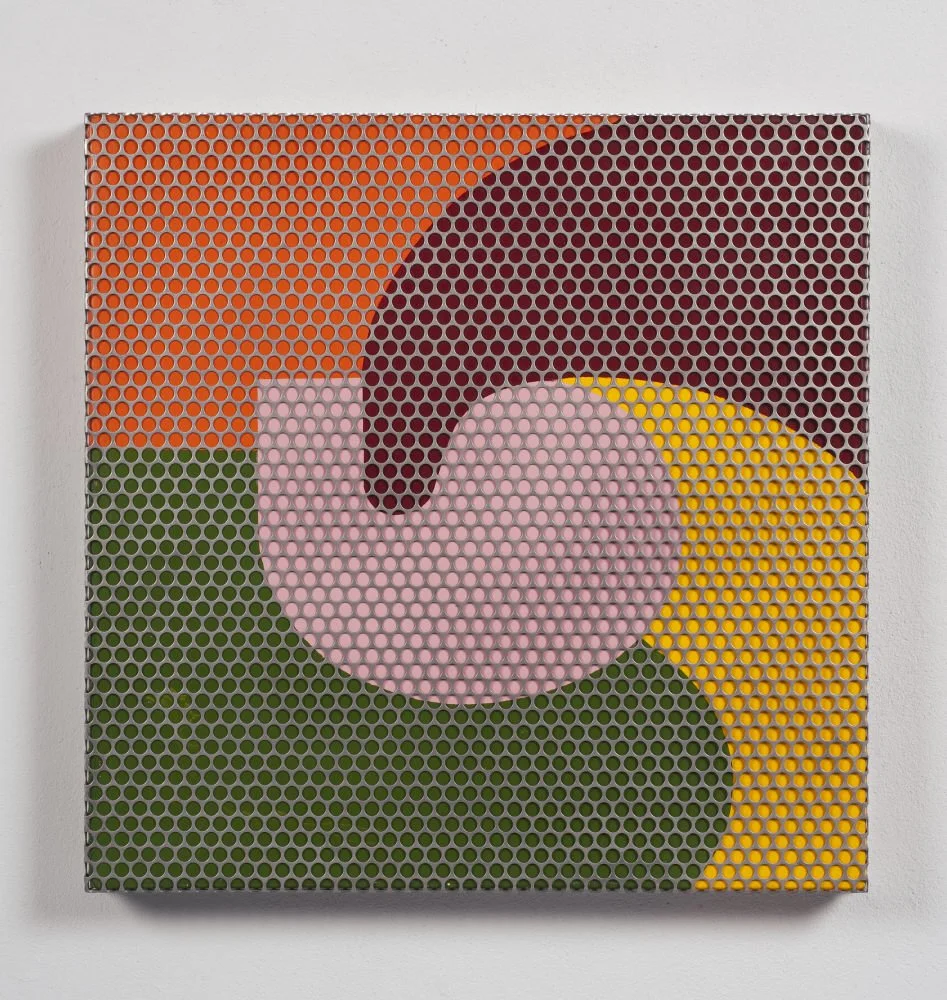

Shapes & Balance

I was quite surprised when I dug into Vasconcelos’ portfolio and found her paintings, but I immediately understood how her understanding of colours and balance came to be. In them you can already see her inclination towards certain shapes that seems to have inspired the form of her Valkyries. She also started using found objects like plastic packaging in her paintings from as early as 1997, which was later expanded on in her installation series Hearts. Comparing the two paintings above, which are created over 10 years apart, one can observe a consistent tone, yet an obvious growth in the complexity of the composition in the more recent piece. They share a similar message (and title) about over-consumption, a theme Vasconcelos holds close to her throughout her practice.

Close-up of plastic cutlery making up Golden Independent Heart, 2004.

Grelha [Grid], 2003

I’ve always held to the belief that exploring different mediums allows you to perceive all mediums with less boundaries, invoking new methods of creation that go on to inform the next work. With Hiperconsumo (2010), her flat colour, hard-edged painting style remains, yet there is a detectable sensitivity to layers; the painting acquires a certain depth, which hints at the compositions of 3D work she has been exploring. Additionally, the transparent packaging is no longer isolated; it reaches the edges of the canvas, forming a deliberate whisper of a texture atop the painting, cleverly suggesting stacked shapes. In other paintings, ‘porous’ materials with repetitive patterns such as metal grids act as a pattern filling the coloured forms. It is perhaps this process of manually layering materials that inspires patterns within a bound shape, such as patterns on a textile, as well as composition of sculptures within a space.

Gateway, 2019. Tiled swimming pool by Joana Vasconcelos, created with 11,366 tiles painted and glazed by hand in a century-old factory in Portugal. The outline of the pool, with its ‘droplet’ edges, is iconically Vasconcelos.

Composition & Space

One of the struggles I feel many textile artists share, is projecting our work into a ‘space’. As most textile crafts begin small (in fact, the finer, the ‘better’), it takes conscious practice to design our work to extend into a space, especially one that is not a fixed cube, or even consider it as part of the architecture like Gateway (2019), a functional swimming pool. Many textile crafts also decorate the ‘surface’ more than suggest form; embroidery, lace-making and macramé, are a few that are popularly created ‘flat’. From where then, does the form spring?

Valquíria #1 [Valkyrie #1], 2004

In 2004, Vasconcelos created her first free-hanging soft sculpture— aptly-named after the Norse mythological figure Valkyrie, often depicted to be flying. The first interpretation of her paintings into a 3D object extending into space had been born. Using crochet and textiles in her work was not new, however; she first introduced soft crochet forms in 2001 with her wall-hanging sculpture, Pantelmina #1 (2001), and Pega #1 [Potholder #1] (2002), and the colour and materiality of this first Valkyrie seemed largely-inspired by those. However, the evolution of its form into a ‘floating’ sculpture gave a new facet to her work, which would later propel her artwork into various unconventional spaces and turn into one of her ‘trademarks’.

Pantelmina #1, 2001. One of Vasconcelos’ first few soft sculptures that was created with crochet. She accentuates the soft quality of the crochet form by binding it with belts, forming bulges that seem to want to escape. She often explores the status of women with her works, and this suggests to me a restriction of soft, feminine power, which finds its strength through malleability.

Pega #1 [Potholder #1], 2002. Similar to ‘Pantelmina’, this soft sculpture (part of a series she terms ‘Pot Holders’) is tacked to a wall, bringing emphasis to the flexibility of crochet and the tension that comes with it.

Raffinée, 2003. An early exploration of scale before the Valkyries series, a blown-up version of Pantelmina #1.

While her wall-hanging soft sculptures seemed to suggest the notion of being ‘trapped’, her Valkyries were the exact opposite; they flew freely, invading spaces unapologetically, forcing one to walk about them. As the series grew, we see the materiality evolve as well. Early on, they seem to emulate her paintings, and borrow from the traditional, folk-crafted pot holder from the kitchen. The Valkyries soon introduced a variety of textures like fringe, tassels, and even lights in the later years, all of which added to the illusion of movement, flight, and a majestic presence.

Mary Poppins, 2010. Installed in the Palace of Versailles in 2012. This exhibition welcomed 1.6 million visitors, a record high in France in 50 years.

Golden Valkyrie, 2012. With a sensitivity to the space inhabited, this Valkyrie introduced metallic elements that brought a sheen; we start to see Vasconcelos’ exploration with new material and the confidence with which she incorporated them, into a form she was growing to be a master of.

Amazônia, 2014. The use of fringe adds almost ‘translucent’ layers and wavering shadows as they move with air currents.

Amazônia, 2014. Ruffled organza trim a part of this Valkyrie that decides not to pay heed to the staircase.

Needless to say, SCALE was of huge importance to her Valkyries series, but not just the overall size. Her prior experience in composition in her paintings probably helped with the balance of shapes and colours. Comparing her first Valkyrie to her later ones, we can see more variety in the size of the patterns as they grew. The earlier crochet works seemed to take the unit size of crochet stitches as they were, making the concentrations of colour quite regular and ‘predictable’. In the later works, the patterns took on random shapes and sizes, breaking away from horizontal and vertical lines, which gave the Valkyries a dynamic quality that appeals to your eye time and again. Most importantly, she had found in the form of the Valkyries what was missing from the ‘Pantelmina’ work even when enlarged— an iconic look that persevered even when rearranged to fit into almost any conceivable space, or changed in colour or materiality; that bulbous, ‘droplet’-shaped form that now extended through vertical stairwells and long, grand halls.

Valquíria Enxoval [Valkyrie Trousseau], 2009. 14m long sculpture exhibited in the Palace of Versailles in 2013. Made in collaboration with the artisans of Nisa, a small countryside village in Portugal known for its rich history of crafts.

It's Raining Men, 2018. Made up men’s shirts and ties, this Valkyrie monstered its way through doorways and corridors of the building.

It's Raining Men, 2018. Lapels, belts, and other elements of menswear is used, yet the Valkyrie form is still distinct.

Materiality & Movement

Blup, 2002. First of her ‘Boxes’ series, an ongoing series which explores crochet forms bulging out from wall-fixed boxes, usually tiled.

Pretty in Pink, 2015. One of her latest pieces from the ‘Boxes’ series, which includes new materials similar to that of her Valkyries. In a way, this seems like a ‘collectable’ Valkyrie, borne of her material explorations in that separate series.

Prior to the introduction of textile materials into her work in 2001, Vasconcelos worked largely with found material, with the closest material to textile being hair— another strong symbol of femininity. Her earlier iterations of crochet sculptures also involved ‘hard’ elements, one of which being tiles, a recurrent material in her work. The exposure to these different objects in her earlier work added to her experience of manipulating different materials and thinking beyond the realms of textile.

Mise, 2000. Vasconcelos often used found objects related to domesticity or femininity.

Una Dirección, 2003. A simple intervention using hair on the Q-poles.

While textile became more predominant in her practice later on, the idea of domesticity and linkage to items associated with the home and womanhood has been an undercurrent from the start. It is perhaps only natural that textile and a home-made craft such as crochet was introduced later on, as she continually questions the fine line between art and domestic labour. While some artists become specialised in the medium they are best known for, it could be the very same thing that binds them in that medium, rendering them unable to ideate outside that capacity. By being led by the artist voice and several strong themes, the work naturally forms a cohesive body of works regardless of medium.

A Todo o Vapor (Verde) [Full Steam Ahead (Green)] #1/3, 2013.

Flores do Meu Desejo [Flowers of My Desire], 1996-2010. One of Vasconcelos earlier works, using the domestic feather duster to form a ‘flower’ wall.

Dorothy, 2007-2010. First conceived in 2007, the ‘Cinderella’ open-toe heel assembled from domestic pots has become one of Vasconcelos’ iconic pieces. It has taken on many iterations under different female names, and displayed in various exhibitions.

One of Vasconcelos’ most known works would be her ‘Shoes’ series, featuring a huge open-toe stiletto made up of the humble, shiny pot you might find in your kitchen. The first of the series named ‘Cinderella’, seems a perfect name for a girl relegated to housework, who then turns into a princess in a shiny dress. The sparkling, humble pots turn into a symbol of elegant womanhood; such juxtaposition is one often played by the artist, who decontextualises items we can easily find in our daily lives to question the contradictions of society.

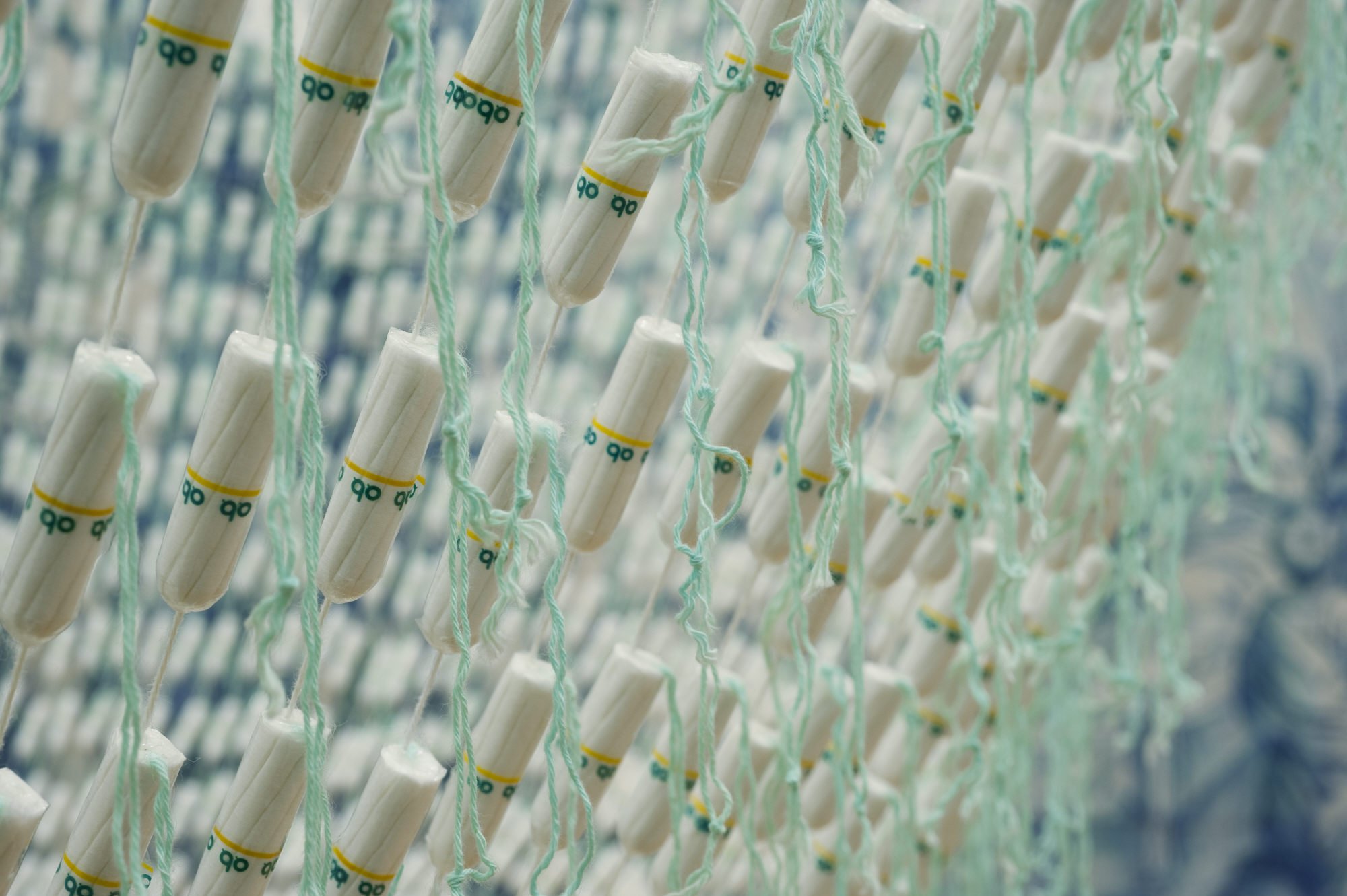

A Noiva [The Bride], 2001-2005.

A Noiva [The Bride], 2001-2005. Close-up showing tampons.

However, my favourite of all her work of assembled readymades must undoubtedly be the cleverly-named A Noiva [The Bride] (2001-2005), which was presented at the Venice Biennale in 2005. Made up of 25,000 tampons, the massive, 6m-tall chandelier must have been a sight to behold at such a grand-scale event, and shocking (in a good way) with its boldness. If it had been a one-off, it might have been a stunt; but her ongoing explorations of the relationship between womanhood and society lend to each other and strengthens her entire body of work.

Some of her assemblages do not directly comment on the usual themes of womanhood; yet they suggest a threatening of this ‘soft energy’ with the overwhelming presence of ‘masculine’ icons often suggesting violence. In War Games (2011), a car wears rifles as its jacket; an array of soft toys sit smiling innocently in it while the rifles on the bonnet point straight into the car, suggesting the innocence that gets in the line of fire more often that not during wars.

War Games, 2011.

Call Center, 2014-2016.

The beauty of readymades is the personality they already have and the connotations that come with it, giving you great tools for making a story. On the contrary, work created from craft (such as many textile mediums) are free to be manipulated in any way, and mostly begin with a blank canvas. Vasconcelos seems to hold an apparent mastery over both, producing works that question society with a clever use of material, and others that simply wow with scale and attention to craftsmanship and sensitivity to colours and form.

Wash and Go, 1998. Silk stockings of all colours hang from two ‘spinners’ that mimic a car wash when you walk through them.

Perhaps, some of my favourite works of Vasconcelos’ are not because they are a form of textile; I am particularly taken by her works that introduce movement. From as early as 1998, she has explored moving parts in her work that accentuate the story she is trying to tell. In Wash and Go (1998), the installation comes to life immediately with movement, making the artwork self-explanatory. It is also this aspect of the artist’s work that I admire— the ability to capture audiences without a lengthy explanation, encapsulating the idea with a very simple title that says it all. It also takes knowledge of material (the type of textile) to predict how it would react when spun; and the effect was truly reminiscent of an actual carwash.

Burka, 2002

This knowledge of and sensitivity to textiles comes through even more in Burka (2002). The set-up is fairly simple— the soft sculpture is lifted slowly in the air, held at the highest point and then suddenly released, making a loud sound as it hits the ground. It is evident Vasconcelos is a great storyteller— the drama and suspense, followed by the climax, and then relief when we remind ourselves this is just fabric, all in under a minute. It takes an understanding of the fabric and how it is put together, to achieve the intended effect so well; first as a clothed human figure (as the name of the work might suggest) as if seated or kneeling, then to one standing up, and finally, at the highest point, a shadow of the gallows. And, in the horror of the falling ‘figure’ in that split second, one cannot help but admire how the fabric billows and reveals all the layers; a thing of beauty, even in death.

Fashion Victims #2, 2018. While there are no videos, pictures suggest this is a kinetic sculpture, as the ‘victims’ were originally completely unbound.

In Fashion Victims #2 (2018), the set-up is clearly inspired by an industrial knitting machine, with the spools of different coloured yarn and feeders; except the naked ‘victims’ are being bound and ‘blindfolded’, instead of having clothes made for them. Consumerism being one of the themes Vasconcelos explores with her work, this suggests how we are becoming victims of the fast fashion world, ‘blinded’ by marketing strategies and bound by trends, to the point we are unable to have the freedom to think for ourselves.

While this art piece does not use textile as its main medium (considering the threads are used without manipulation), its form suggests a knowledge of the technicality behind textile production, starting a conversation about textile and its fate in the current world, without actually engaging in a textile practice.

Recontextualising

Matilha [Pack of Dogs], 2005

Prior to encountering the Royal Valkyrie in the Royal Academy that fateful Summer’s day, I had unknowingly come across Vasconcelos’ work online; but as the Internet these days go, there was either no credit or I did not remember it. Seeing these images of ceramic sculptures covered in crocheted doilies brought back the memory immediately.

I’d think most people who crochet enjoy making doilies. They are pretty, technically challenging, therapeutic… but there’s only so much you can do with doilies. This is one of the reasons doilies are a popular choice to go with in yarnbombing, along with the fact that they come in loose pieces and can easily be manipulated through sewing to ‘wrap’ an unevenly-shaped object.

Gorette, 2006

I don’t think I can say with as much confidence though, that everyone can wrap a considerably small object (with many protrusions at that) with such precision and artistry. In Gorette (2006), the symmetry and choice of doilies in different sizes and styles is obviously a result of long deliberation and planning. It is with these pieces that the artist’s eye for quality and respect for craftsmanship comes through.

Enamorados [In Love], 2005. The urinal series by Vasconcelos is a symbol of feminism and also gay love.

It is not just traditional, white doilies she explores though; Vasconcelos has a series of Urinals wrapped in crochet of all colours and styles, an ode to Marcel Duchamp, who she considers ‘the master of contemporary thought in sculpture’, and a huge influence in the usage of readymades in her work.

Putting two urinals together and joining them up with crochet, Vasconcelos sees these works as a symbol of feminism and also gay love. While covering readymades in crochet is not a new practice, her choice of object gives the work her voice. Lace, with its intricacy, connotations of domestic labour and sympathetic quality, easily overrides the original personality of an object, and the artist cleverly makes use of this trait to recontextualise these common objects and imbue them with a new personality.

Minerva, 2005

While Vasconcelos’ portfolio extends far beyond my writing, I wanted to follow her journey from the start to understand the origins of her work, and try to observe it from the perspective of a textile practitioner. I started writing this article in May 2021, and am only finishing it in October 2022, because her portfolio was so extensive that I was exhausted just going through everything!

It was truly enlightening to research Joana Vasconcelos, and it affirms my beliefs that an artist with a consistent voice can only be so through lots of experience, dedication and an openness to all mediums. It’s difficult to become a master of your medium, or have a strong artist voice and concepts, but much more difficult to be able in both.

“Materials and techniques serve the needs of artists as a result of intention and choice, not by happenstance or accident. The making of art is dependent on a series of choices as to how and when to utilise a specific material, and how best to transform material— to give it form— through specific behaviours and actions.”

Regaining a Sense of Purpose with Slow Art

A written version of the speech I delivered for TEDxCMU in 2022.

Faig Ahmed

Wave Function, 2016. Image Courtesy of Faig Ahmed Studio

Faig Ahmed has exhibited across continents and already been extensively featured, but he makes a great choice for this first feature. Hailing from Baku, Azerbaijan, he graduated in 2004 from the sculpture program at the Azerbaijan State Academy of Fine Arts, and showed in Azerbaijan’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennale just 3 years later.

Pictured above are some of his contemporary carpet sculptures, which has become what he is best known for. However, his work transcends sculpture, and has included large-scale installations as well as performance art.

Perhaps one of the most impressive elements of Ahmed’s famous carpet sculptures are his insistence on traditional Azerbaijani weaving techniques. He works with a group of skilled weavers to produce his pieces, which have been digitally distorted on computers.

Easy access to computer programs have now created a saturation of ostentatious digital or digitally-modified works, but Ahmed’s sculptures use this not as the medium, but as a means of elevating this ancient craft. Carpet weaving has existed for centuries and already wowed many with the intricate craftsmanship and techniques passed down through generations; Ahmed maintains the delicate balance of breaking the traditions, cultures and archetypes we associate with this cultural motif while still remaining respectful of its heritage.

Traditional Azerbaijani Carpet Weaving Art

(Source: artsandculture.google.com)

In order to look beyond Ahmed’s visual language, we have to have a little context about this ancient craft.

The first Azerbaijani carpets appeared in the Bronze age according to historians, and is one of the richest carpets in the world due to its size, number of characters and patterns, and colour tones. Their distinguishing feature is the high density of nodes (from 1,600 to 4,900 per square decimeter), which is why the “lifespan” of the Azerbaijani carpet is from 300 to 500 years. In 2010, “The traditional art of Azerbaijani carpet weaving art” was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

These carpets have been praised in historical writings, classical literature and folklore writing, and even depicted in Renaissance paintings to draw attention to a figure of importance. The symbols and patterns in the carpets can be regarded as an alphabet, and various cultural discoveries or events in history can be interpreted by studying them. Techniques on carpet weaving are usually passed verbally from generation to generation in secrecy, and despite being used in everyday life in home furnishings, holds great significance to the society. Special carpets are woven for every significant event from childbirth, to weddings and worship rituals, and cutting a finished carpet from the loom is a special celebration.

Still Life with a Jug with Flowers, late 15th century, Hans Memling

Painting from the late 15th century depicting a woven carpet of Azerbaijani origins

Mugan carpet, Karabakh school, late 14th to early 15th century, Azerbaijan Carpet Museum

The traditional carpets are handcrafted through a process involving different members of the family from the very beginning. Men help to shear the sheep and collect wool in autumn and spring, while women gather herbs for different coloured natural dyes. The sheep which provide this wool is specially taken care of, and not allowed to graze freely, resulting in a long and clean fleece. (Source: UNESCO Youtube Channel)

The wool is then spun into yarn, and grandmothers and mothers guide the younger ones in the weaving in the winter months.

The weaving process includes warping the loom, threading the yarn through the warp yarns, combing them down, and finally hammering them down to make each knot compact. As Ahmed mentions in ‘Equation’ (Film by Neta Norrmo), the tension of every knot can be heard as the weavers knock them down, and each ‘dot’ on the carpet is a concentration of human power.

As someone who has no background in weaving, I can only make superficial observations of the process. The one thing that stands out to me is how the Azerbaijan technique uses a vertical loom (similar to a tapestry loom), with warp yarns running ceiling to floor; in other weaving processes I have seen, from the small rigid heddle loom to the Japanese Saori floor loom, the loom is usually laid horizontally.

The horizontal looms also usually have a ‘shed’, which is formed when the alternate warp yarns are separated for the shuttle of weft yarn to be fed through. This makes the weaving process a lot more efficient.

From the videos featuring Azerbaijan weaving, it seems as if the loom is so basic that its main job is to hold the warp yarn. For the piled carpets, each sliver of dyed wool is individually hooked onto the warp yarn, then hammered down with a tool to keep it compact. This means each ‘pixel’ of the pattern on the carpet is literally created one by one. It is extremely time consuming, and the position of the loom makes it uncomfortable for the weaver as they have to adjust their height following the progress of the weave.

This rigorous process is followed closely in every household, and it is apparent that these carpets hold a very special meaning to the society aside from just being decorative items. As someone who originated from this heritage, it might actually have been more difficult for Ahmed to break tradition as it requires a mental shift to view the familiar as otherwise. One of the earliest memories Ahmed had was cutting apart a family rug simply because he wanted to rearrange the pattern (Source: Forbes.com); perhaps, it is a show of how differently Ahmed regarded these rugs from a young age.

it is also a challenge for the weavers who are used to traditional motifs and methods, to accept these digital manipulations and trust in Ahmed’s vision. In a way, they are each like a knot in the pattern, playing a very important part in the larger scheme of things.

Highlights of video Social Anatomy (2016)

Director: Faig Ahmed